Photography soon displaced semi-mechanical methods such as the physionotice-engraved portrait (which nonetheless can be considered its ideological precursor) and also artistic techniques such as pictorial miniature. Invented by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in the third decade of the 19th century, it was not until the substantial modifications introduced in the 1930s by another Frenchman, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, that a practical procedure (the daguerreotype) became available to reproduce reality thanks to the action of light on a photosensitive surface.

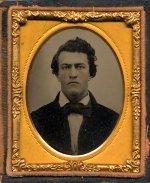

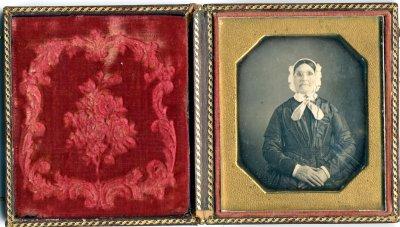

A daguerreotype is a direct positive on a copper plate bathed in silver and sensitized with iodine vapors that initially required an exposure time of close to sixty minutes.

In the 1940s, daguerreotype shared the limelight with the calotype or talbotype (named after its inventor, the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot), a method that produces a negative on paper sensitized with silver nitrate and gallic acid from which positives are obtained on paper: this multipliable image character makes it the first modern photographic process.

In the 1850s and 1860s, ambrotypes on a glass support, tinplate panotypes, and panotypes on cloth, oilcloth, and other fabrics appeared, prepared in wet collodion, as well as the albumen positives derived from the negatives in glass plate.

The gelatin-bromide dry plate (a glass plate covered with a solution of bromide, water, and gelatin) paved the way for instant photography. It was created in the 1970s and its use became general in the 1980s when the industrial manufacture of paper began to print gelatin-bromide as well. In fact, this has been the hegemonic process to this day. The Museum has original pieces that illustrate most of the procedures described.